The Search for Vulcan: How a Phantom Planet Led to General Relativity

The Search for Vulcan: The Phantom Planet That Led to General Relativity

Throughout history, science has been shaped by both brilliant discoveries and persistent misconceptions. One such astronomical enigma was the hypothetical planet Vulcan, which for centuries was believed to exist within the orbit of Mercury. Although it was ultimately debunked, the search for Vulcan played a crucial role in the development of modern physics—leading directly to Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

The Origins of the Vulcan Hypothesis

The story of Vulcan begins in the early 17th century, shortly after Galileo’s telescopic observations were revolutionizing the solar system. Reports of dark objects transiting the Sun sparked speculation about an undiscovered planet orbiting even closer than Mercury. In 1611, astronomer Christoph Scheiner documented black spots moving across the Sun, later identified as sunspots. However, the idea of an intra-Mercurial planet persisted for centuries.

The concept gained serious traction in the mid-19th century when Urbain Le Verrier—the astronomer who accurately predicted the existence of Neptune by studying Uranus’s orbit—turned his attention to Mercury. He noticed peculiar deviations in Mercury’s orbit that Newtonian physics could not explain. Given his previous success, Le Verrier proposed that an unseen planet, Vulcan, was perturbing Mercury’s motion, just as Neptune had explained Uranus’s oddities.

Observations and Controversial Confirmations

Le Verrier’s hypothesis led to widespread searches. In 1859, an amateur astronomer named Edmond Modeste Lescarbault claimed to have observed Vulcan crossing the Sun’s disk. Encouraged by this report, Le Verrier publicly announced the planet’s existence. Many astronomers attempted to verify the claim, but results were inconsistent: some saw the alleged planet, while others saw nothing at all.

Even though exhaustive searches in the 1860s and ’70s failed to confirm Vulcan, the theories persisted. Notably, during a total solar eclipse in 1878, two distinguished astronomers—James Craig Watson and Lewis Swift—independently reported a reddish celestial body resembling a planet inside Mercury’s orbit. Despite initial excitement, their observations lacked reproducibility, and no subsequent eclipses ever revealed Vulcan again.

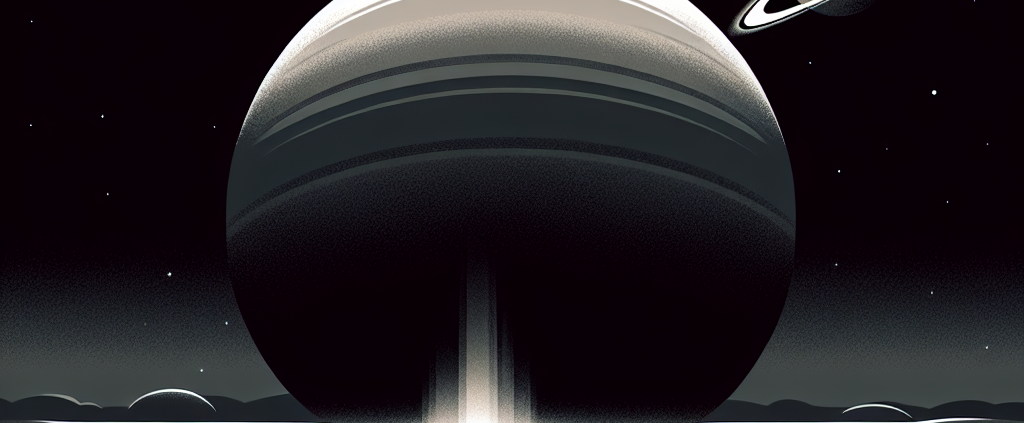

Image: [1,19th century astronomer observing the Sun with a telescope]

The Death of Vulcan and the Birth of General Relativity

The mystery remained unresolved until the 20th century, when Albert Einstein provided the ultimate explanation. In 1915, Einstein’s theory of general relativity fundamentally altered our understanding of gravity. Instead of treating gravity as a conventional force acting in a straight line (as Newton did), Einstein proposed that massive objects like the Sun curve space-time itself. This curvature affects planetary orbits in subtle but observable ways.

When Einstein applied his equations to Mercury, he found that general relativity accurately described the planet’s peculiar orbital movement—eliminating the need for Vulcan altogether. The phantom planet was no longer necessary to account for Mercury’s motion, and its existence was officially discarded by the scientific community.

Might Hidden Vulcanoids Exist?

Although Vulcan proved to be a myth, the possibility of small asteroid-like objects within Mercury’s orbit—dubbed “Vulcanoids”—remains an open question. These hypothetical bodies, if they exist, would be difficult to detect due to their proximity to the Sun, where the intense glare complicates direct observation.

Modern searches using space telescopes and missions like NASA’s Parker Solar Probe have yet to uncover evidence for Vulcanoids. However, astronomers remain interested in surveying Mercury’s neighborhood for remnants of primordial planetary formation. If such objects exist, they could represent some of the oldest material in the solar system.

Image: [2,NASA Parker Solar Probe data imagery near the Sun]

Could Vulcan Have Been a Primordial Black Hole?

Today, Vulcan exists only as a historical curiosity, but a surprising new theory has resurrected its name in an unexpected way. Some physicists speculate that rather than a planet, something truly exotic could reside in the Sun’s inner domain—a tiny primordial black hole.

Primordial black holes are hypothetical remnants of the early universe, formed in extreme density fluctuations shortly after the Big Bang. If one had been captured within the solar system, it could theoretically inhabit a stable orbit inside Mercury’s path. Though this idea is speculative, modern astronomy has begun exploring ways to detect such objects via microlensing events and other observational techniques.

This notion even recalls a fascinating idea from Stephen Hawking in 1971, who suggested that a primordial black hole could reside at the Sun’s core. While this was originally proposed to explain discrepancies in solar neutrino observations (which have since been resolved through particle physics), the thought experiment remains intriguing.

Image: [3,An artistic visualization of a primordial black hole near the Sun]

Conclusion

Although Vulcan was ultimately a figment of astronomical imagination, it played an invaluable role in advancing science. Its supposed existence forced astronomers to question Newtonian physics, setting the stage for Einstein’s revolutionary insights into gravity. Today, its legacy endures not as a planet, but as a stepping stone toward one of the most profound discoveries in human history—general relativity.

The search for Vulcan reminds us that scientific progress is often born from mistaken ideas. By investigating anomalies and challenging conventional wisdom, we push the boundaries of our understanding, revealing the true nature of the universe one discovery at a time.

Vulcan’s story is a fascinating reminder of how scientific discovery is shaped by both persistence and revision. The pursuit of this nonexistent planet ultimately revolutionized physics.