The Origins, Expansion, and Reasoning Behind Christianity

Christianity, one of the world’s most influential religions, traces its origins to the early 1st century CE in the Roman province of Judea. Its evolution from a small sect within Judaism to a global faith with billions of adherents is a story shaped by spiritual beliefs, political ambitions, cultural exchanges, and historical circumstances. This exploration delves into the origins, expansion, and reasoning behind Christianity, emphasizing its role in shaping societies and governance.

Origins of Christianity

Christianity is deeply rooted in Jewish religious traditions, emerging as a sect within Judaism during the 1st century CE. It was heavily influenced by Jewish scripture, including the Torah and prophetic writings, which foretold the coming of a Messiah—a savior who would restore Israel and bring about divine justice.

Jesus of Nazareth, a Jewish preacher and teacher, was seen by his followers as this long-awaited Messiah. His teachings emphasized love, forgiveness, and the kingdom of God, presenting a reinterpretation of Jewish law that prioritized compassion over ritual. Around 30-33 CE, Jesus was crucified under Roman authority, a punishment for what was seen as a challenge to both religious and political order. However, his followers believed that he rose from the dead three days later, affirming his divine mission and identity as the Messiah.

Connection to the Age of Pisces

Some interpretations link the rise of Christianity to the astrological Age of Pisces, which began around the time of Jesus’ birth. Pisces, symbolized by the fish, is often associated with spirituality, compassion, and sacrifice—themes central to Jesus’ teachings. The fish also became an early Christian symbol, used by believers to identify themselves discreetly during periods of persecution.

Though Jewish prophetic writings do not explicitly reference the Age of Pisces, the socio-cultural environment of the 1st century CE may have made the notion of a Messiah more compelling. Astrological associations with a new age—characterized by renewal and spiritual transformation—may have coincidentally aligned with Jewish hopes for a deliverer. The Roman occupation and widespread disenfranchisement of the Jewish people also heightened expectations for a savior who could restore Israel. Jesus’ coincidental birth during this astrological period may have added symbolic weight to his message, helping some to perceive him as fulfilling long-standing prophecies.

Key Figures and Early Spread

- The Apostles: Jesus’ disciples, particularly Peter and Paul, played crucial roles in spreading his teachings. Paul, a former Pharisee, extended Christianity beyond Jewish communities, preaching to Gentiles (non-Jews) across Asia Minor, Greece, and Rome.

- Early Christian Communities: Small, decentralized groups gathered in homes to worship, sharing a message of salvation and equality that appealed to marginalized populations, including slaves and the poor.

Despite its initial growth, Christianity faced persecution from the Roman authorities for its refusal to worship the emperor or participate in traditional pagan practices. These challenges, however, only strengthened the faith’s resolve and identity.

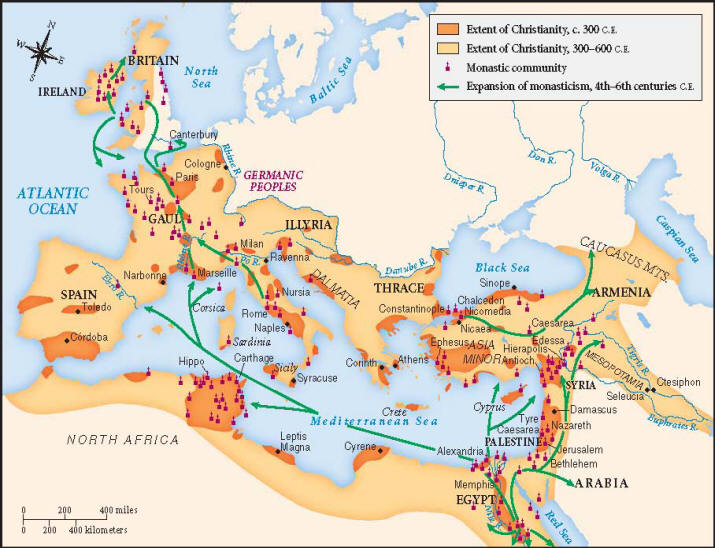

Expansion of Christianity

The spread of Christianity unfolded in several phases, marked by both peaceful missionary work and forced conversions. This expansion transformed the religion into a powerful socio-political force.

1st–4th Centuries: The Roman Empire

- Missionary Activity: Paul and other apostles established Christian communities throughout the Mediterranean. These communities grew despite sporadic persecutions, such as under Emperor Nero.

- Legalization and Adoption: The turning point came in 313 CE with the Edict of Milan, issued by Emperor Constantine, which legalized Christianity. Constantine’s conversion marked the beginning of Christianity’s alignment with political power.

- State Religion: In 380 CE, Emperor Theodosius I declared Christianity the state religion of the Roman Empire through the Edict of Thessalonica, outlawing pagan practices and forcing many to convert.

5th–11th Centuries: Europe and Beyond

- Medieval Europe: Missionaries like St. Patrick in Ireland and St. Augustine of Canterbury in England peacefully converted local rulers and their peoples. However, rulers like Charlemagne used force to convert the Saxons, punishing those who resisted.

- Eastern Expansion: Christianity spread to Eastern Europe through the conversion of Kievan Rus in 988 CE under Prince Vladimir I, who embraced Eastern Orthodoxy to unify his realm.

12th–15th Centuries: Crusades and Reconquista

- The Crusades: Christian campaigns to reclaim the Holy Land often involved forced conversions of Jews and Muslims. In Northern Europe, the Baltic Crusades targeted pagan tribes for Christianization.

- Spain and Portugal: During the Reconquista, Muslims and Jews in Spain were given the choice of conversion, exile, or execution under Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella.

16th–19th Centuries: Age of Exploration

- The Americas: Spanish and Portuguese colonizers used Christianity to justify conquest and forcibly converted Indigenous peoples. Missionaries accompanied settlers, blending religious and cultural domination.

- Africa and Asia: Christian missions spread to sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, often tied to European colonial enterprises. In regions like Goa, forced conversions of Hindus and Muslims were carried out under Portuguese rule.

- Pacific Islands: Christianity’s expansion into Polynesia and Micronesia was facilitated by Western colonial influence and missionary efforts.

20th–21st Centuries: Modern Growth

- Global Missions: Christianity grew rapidly in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia through voluntary conversions, aided by missionary organizations.

- Post-Colonial Influence: In formerly colonized regions, Christianity remained a dominant force, intertwined with cultural identity and social institutions.

Reasoning Behind Christianity’s Spread

Cultural and Religious Appeal

- Universality: Christianity’s message of salvation and equality appealed to marginalized groups, offering hope and a sense of purpose.

- Moral Framework: Its ethical teachings, centered on love, forgiveness, and justice, resonated with diverse audiences.

- Community: Early Christian communities provided support networks and a sense of belonging, especially in times of social upheaval.

Political and Social Utility

- Unifying Ideology: Christianity helped rulers consolidate power by promoting a single belief system. For example, Emperor Constantine used Christianity to unify the fracturing Roman Empire.

- Moral Legitimacy: Rulers aligned with the Church gained divine authority, justifying their reign as part of God’s plan.

- Governance: The hierarchical structure of the Church mirrored and supported state administration, providing a framework for societal control.

Economic and Geopolitical Motives

- Wealth and Influence: The Church’s control over vast lands and resources made it a significant economic power.

- Colonial Justifications: European powers used Christianity as a moral rationale for conquest, framing colonization as a duty to “save” heathen souls.

- Trade Networks: Shared religious values facilitated trust and cooperation among merchants, bolstering economic activity.

Coercion and Force

While many converted voluntarily, forced acceptance played a significant role in Christianity’s expansion:

- Roman Empire: Pagan practices were outlawed under Theodosius I, compelling subjects to adopt Christianity.

- Charlemagne’s Campaigns: Saxons were baptized under duress, with severe penalties for resistance.

- Colonial Conquests: Indigenous peoples in the Americas, Africa, and Asia were often coerced into Christianity through violence and cultural suppression.

Christianity as a Political Tool

Christianity’s alignment with political ambitions is evident throughout history:

- Roman Empire: Constantine’s conversion and Theodosius’ declaration turned Christianity into a state-sanctioned religion, consolidating imperial control.

- Medieval Europe: The Church wielded immense influence, with popes often acting as kingmakers. Charlemagne’s forced conversions unified his empire under a Christian identity.

- Colonial Era: Christianity legitimized European domination, framing colonization as a spiritual mission.

Conclusion

Christianity’s journey from a small sect in Judea to a global faith reveals its adaptability and profound influence on societies. While its spiritual teachings have inspired billions, its spread was often shaped by political and economic forces. Rulers, empires, and institutions used Christianity to unify diverse populations, justify conquests, and consolidate power. Understanding Christianity’s history requires acknowledging both its spiritual appeal and its role as a socio-political construct, highlighting the intricate interplay between faith and power in human history.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!